Animals that eat jellyfish also eat plastic bags

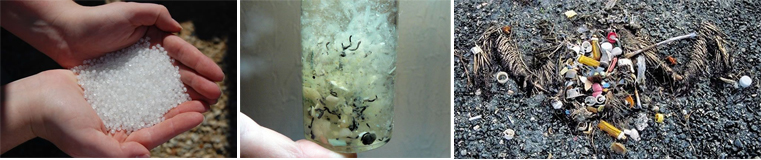

Animals that eat plankton or fish eggs also eat plastic pellets

Animals that eat fish also eat plastic.

MSNBC posted a story on April 9, about leatherback turtles’ diet of plastic bags.

A new study looked at necropsy reports of more than 400 leatherbacks that have died since 1885 and found plastic in the digestive systems of more than a third of the animals.

Leatherback turtles are critically endangered and highly charismatic creatures. They are big, weighing 1,000 pounds or more, with shells that can measure more than 6 feet across. These peaceful creatures have had the same basic body plan for 150 million years.

Leatherbacks are also popular for what they eat: namely, large quantities of jellyfish. The problem is that plastic bags look a lot like jellyfish, and plastic often ends up in the oceans, piling up in areas where currents — and turtles — converge.

Plastic can block a turtle’s gut, causing bloating, interfering with digestion, and leading to a slow, painful death. “I can’t imagine it’s very comfortable,” he said. “Their guts weren’t designed to digest plastic.”

There are vast fields of trash floating in the world’s oceans, Sasso added. And leatherback turtles travel thousands of miles each year, giving them even more opportunities to come in contact with it.

“This is an animal that has survived many extinction events,” James said, “And now it’s got all these anthropogenic hazards to face.”

And there’ve been a spate of publications on the amount of plastic – both nurdles, which are plankton or fish-egg -sized industrial plastic pellets from manufacturing shopping bags, dollar-store articles, and construction material that ends up in the oceans, and consumer plastic (bottles, bags, buckets, etc), which breaks down into ever-smaller pieces but does not completely degrade. This stat is from 2001:

There is now six times more plastic debris in part of the North Pacific Ocean than zooplankton, the populous animal plankton that forms the base of the aquatic food chain.

– C. J. Moore, S. L. Moore, M. K. Leecaster and S. B. Weisberg (December 2001). “A Comparison of Plastic and Plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre”, Marine Pollution Bulletin 42)

Granted this statistic has been rejected because it only reflects an analysis made in the Pacific Gyre, a confluence of currents and thus a concentration of the contents of what’s carried on them; but even so, the volume of plastics is not decreasing. Some solutions: don’t take plastic bags, get refillable canteens for water. Reconsider the purchase of synthetics which may discharge plastics on the manufacturing process. Consider what else you can do with the plastics you are about to throw in the garbage.

If fish are eating plastic nurdles, then so are we if we eat fish.

Here’s more nurdle info:

http://www.nurdlesaretheenemy.com/

http://theurbancoaster.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=179&Itemid=92&lang=en

http://ewasteguide.info/more-plastic-plankto